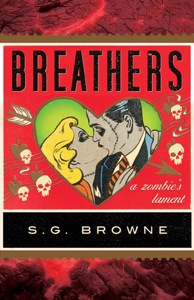

I the first part of my review, I wrote about the werewolf poem-novel Sharp Teeth by Toby Barlow. In it, he writes: “still conscious, a little hungrier. / It’s a raw muscular power, / a rich sexual energy / and the food tastes a whole lot better.” This would have fit in great in Breathers (Broadway Books).

Warning! This post will contain spoilers. Since zombies are involved, this is inevitable.

I remember a few years back reading Mary Roach’s Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers, thinking, “Some day, a sharp fiction writer is going to put all this info to good use.” That’s exactly what S.G. Browne has done with Breathers. This is no great insight on my part; he’s said as much several times. But even if he hadn’t, I would have recognized her ideas in his work: plastic surgeons practicing on severed heads, formaldehyde in cosmetics, fun stuff like that.

While the occasional reference to this or that familiar scientific use of cadavers was no shock, plenty in Breathers took me by surprise. Funny to say, but in a book about zombies, the best bits weren’t about rotting or eating yummy brainses. Breathers is about empowerment and identity. Through eating people.

I expected Breathers to fall mostly into Christopher Moore territory. Light-hearted supernatural comedy. Though it’s not entirely unlike Moore’s work, the book Breathers reminds me most of (other than Stiff) is Fight Club. Investigating the book after I read it, I found that this is a comparison Browne himself has made, citing Chuck Palahniuk as an inspiration in more than one interview.

(Lest any of you get the wrong impression, there are no shirtless zombie brawls, auto-pugilism or sadomasochistic soap-making lessons.)

Palahniuk may roll his eyes at my assessment, but my take on Fight Club is that it tries to answer how men construct a concept of masculinity when there are no meaningful examples upon which to draw. The nameless narrator, self-effacing, emasculated and powerless, creates an uber-masculine alter ego (or perhaps, alter id) Tyler Durden, because his understanding of what it means to be a man is polarized, trapped in the roles of victim and victimizer. The narrator finds a brand of empowerment through violence, beginning with literally fighting himself.

Palahniuk may roll his eyes at my assessment, but my take on Fight Club is that it tries to answer how men construct a concept of masculinity when there are no meaningful examples upon which to draw. The nameless narrator, self-effacing, emasculated and powerless, creates an uber-masculine alter ego (or perhaps, alter id) Tyler Durden, because his understanding of what it means to be a man is polarized, trapped in the roles of victim and victimizer. The narrator finds a brand of empowerment through violence, beginning with literally fighting himself.

Susan Faludi referred to the film version of Fight Club as “a quasi-feminist tale, seen through masculine eyes.” Fight Club, as I see it, shows the need for masculine self-definition, though in the narrator’s case, some of methods he utilizes are pretty fucked up.

The best definition of feminism I know is the one my mom told me when I was a kid: it’s the right of women to define themselves. Feminism seeks to shed forced definitions of what it means to be a woman. And as I see it, you can’t lie to one gender without the other getting lied to as well. Male identity is also clouded by sexism, the very same sexism that undermines a woman’s view of herself. Are men to be providers or thieves? Passive or aggressive? Gentle and respectful or beasts? As feminism seeks to undo objectification in women, men consequently must also examine their gender identity.

Part of the answer is, of course, that human beings are simply too complicated to categorize in polar archetypes. No one is a pure villain or hero. Nobody conforms entirely to stereotypes. But the archetypes remain in the popular imagination as generalities to explore. I think it’s natural to investigate gender through speculative and allegorical fiction.

(Side note: Faludi’s assessment is, in and of itself, intriguingly problematic. Female search for self-definition we call feminist. The same in men we call quasi-feminist. See what I mean?)

In Breathers, Browne chooses to make zombies sentient and offers no particular explanation for where they come from. They just are. Investigating supernatural phenomena is not a major concern in Breathers. How much it sucks to be a zombie is a much bigger deal. Zombie existence is a state of pervasive impotence. They’re weak and hated, part leper, part disabled and all-purpose victim. It’s socially accepted to ridicule them as slow and smelly and gross. People love to throw things at them. Fratboy gangs (who, in a clever reversal, are described in a manner evocative of the undead hordes in zombie films) roam the streets looking for zombies to kill. Zombies have no rights at all. They are the nightmare of emasculation.

But surely Breathers is about rotting corpses, not masculinity, right? There are female zombies, right? Yes, I counted three women among the several named zombie characters. Only two of the three are of any importance. Helen runs the Undead Anonymous support group and the other is Andy’s (the protagonist and narrator) girlfriend, Rita. I point this out not as a criticism of the book but rather to indicate the prevalence of male perspective in it. Is it a huge leap to say a book that’s almost exclusively masculine in viewpoint is, in and of itself, about male experience? I don’t think so.

Not to put too fine a point on it, I’m saying that in Breathers, zombie = castrated male. And in Fight Club, that’s what the narrator was, too. And both books center on the narrators’ violent and generally aberrant ways to regenerate some mojo. In both, support groups don’t address the real problem, and neither does romance (in this, the books take divergent approaches. Fight Club‘s Marla is sex and no love, Breathers’ Rita is mostly love and no sex at first).

The solution to powerlessness presented in both books is to reject monstrous ineptitude by embracing a destructive act. In Breathers, zombies are told that eating human flesh is just folklore, that zombies don’t actually do it. But this is a lie. As Andy and the other zombies discover, eating people makes you strong and healthy and sexually active. A zombie, weak and shabby, is no threat to the world that shuns him. The same goes for the guys in Fight Club. But by embracing the violent acts they’ve been told all along are aberrant, they feel better. While I in no way espouse violence, I can only think that there’s a natural desire, in dismantling someone else’s definition of you, to reach out for the acts that the hegemony despises.

The solution to powerlessness presented in both books is to reject monstrous ineptitude by embracing a destructive act. In Breathers, zombies are told that eating human flesh is just folklore, that zombies don’t actually do it. But this is a lie. As Andy and the other zombies discover, eating people makes you strong and healthy and sexually active. A zombie, weak and shabby, is no threat to the world that shuns him. The same goes for the guys in Fight Club. But by embracing the violent acts they’ve been told all along are aberrant, they feel better. While I in no way espouse violence, I can only think that there’s a natural desire, in dismantling someone else’s definition of you, to reach out for the acts that the hegemony despises.

I might be guilty here of making Breathers sound a whole lot more serious than it was meant to be. And there are a lot of great laughs, moments of tenderness and memorable characters. I don’t want to misrepresent it. But to look at it only in terms of undead romantic comedy would be ignoring a great deal of its meaning.